War is Hell!

The Lessons learned by Ken Burns . . .

Legendary film-maker Ken Burns was credited as saying something to the effect that once he got into researching and producing his famous Civil War documentary series, he became overwhelmed by the sheer volume of stories — long forgotten in letters, books and personal effects. He lamented that he had to “shut the door” on taking on more content in order to wrap up the series . . . material just had to hit the “cutting room floor” and he had to call it “wrap.”

Well, we reached that point some time ago!!! But we are looking at the work and the research accomplished so far to be an inspiration for further writing and perhaps a serious dalliance into film . . .

General William T. Sherman, the Union General who marched 70,000 men through Atlanta and the Carolinas, and who accepted the surrender of the Army of Tennessee in Durham, NC, famously said

“war is hell”

War is also as expensive as hell — and meeting the challenge of funding the “cruel exigencies of war” required almost super-human feats of politics and financing (and arguably even some “conjuring”) to achieve in the War — for both the North and the South.

Because of the War — and the insatiable need for money — monumental changes were wrought during the “Ten Tumultuous Years” (1857 – to – 1867). In the North, there were sweeping legislative Acts that changed the rules of public financing so that previously unimaginable sums of money could be raised (and ultimately repaid somehow).

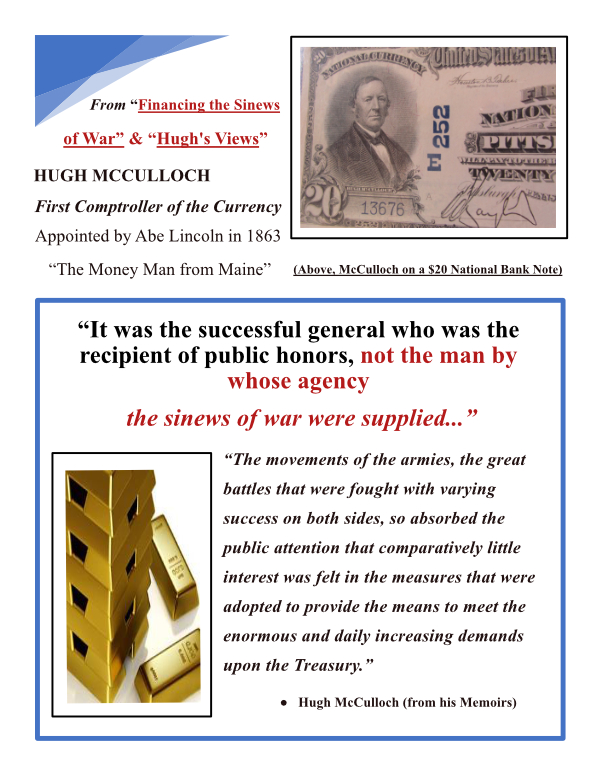

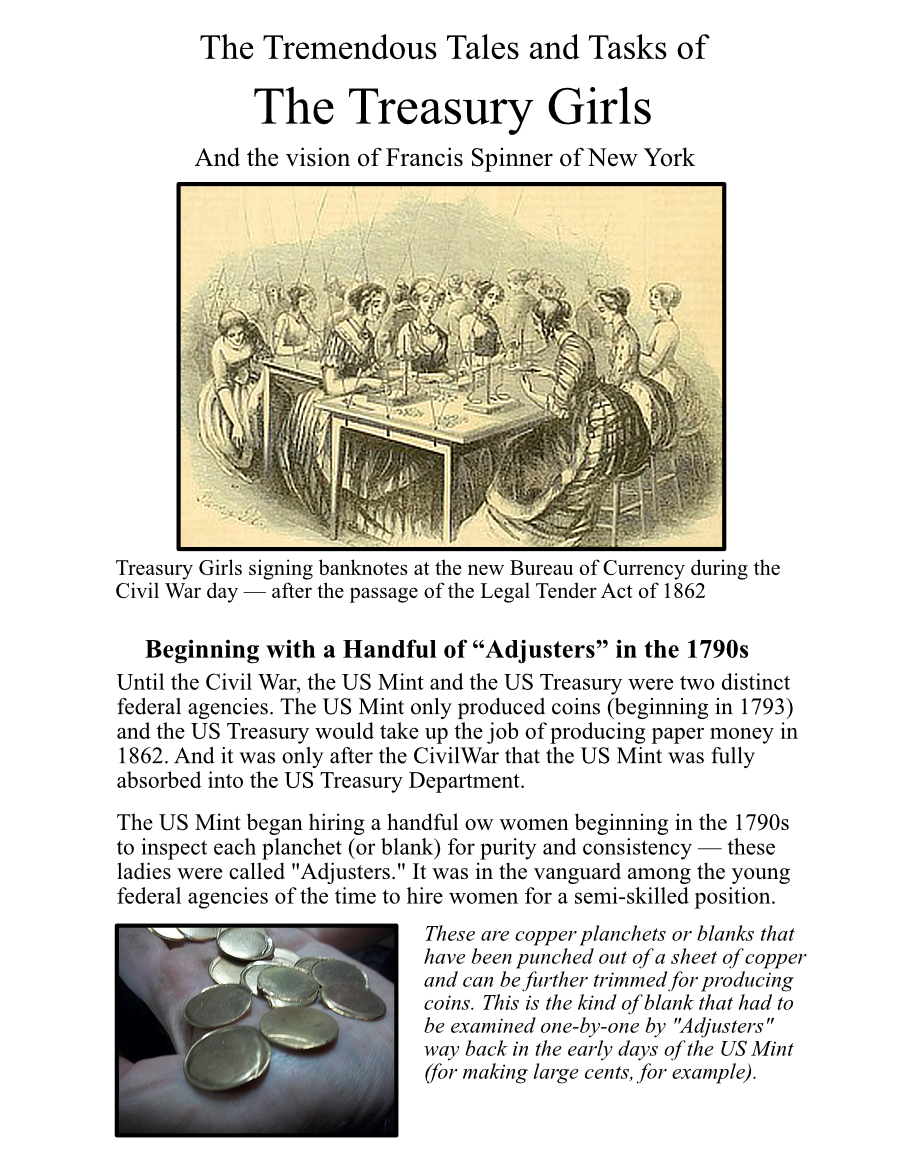

Here is a glimpse of the US Treasury’s situation in 1860, just before the War of the Rebellion started: The entire revenue for the federal government was about $30 million (and that was $5 million short); most of the money came from tariffs collected from the maritime trade. By the time the War was in full gear, around 1863, the Union expenses were running at about ONE MILLION dollars PER DAY. The Secretary of the Treasury, Salmon Chase, and his right-hand man, Hugh McCulloch, plus certain members of the Congress, cooked up novel ways to raise massive amounts of money that were considered “heretical” by some. These Acts included the Legal Tender Act and the National Bank Act, which transfigured our money and banking for decades to come . . . and gave birth to the Internal Revenue Service, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) and the US Secret Service.

Cornelius Vanderbilt — industrialist and “Robber Baron” — would state that Rep. Elbridge Spaulding, of New York “conjured money out of nothing.” Spaulding is credited with pushing the Legal Tender Act through the US Congress in 1862, creating federal paper money that one Act — which was never rescinded (though it was a “war-time measure”) created both a uniform federal currency and “an interest-free loan.” In the wake of the War, there was even a Legal Tender Party, which became quite active a decade after the War ended — and at one point, a well-known former Union General named Ben Butler actually ran for president on that ticket — the party never had a president elected on its ticket, but it helped keep paper money on as “legal tender currency,” effectively lasting to this day.

In the South, once the Confederate Government was established, all of the federal assets in the seceding States were “taken in trust” (basically confiscated) by the Confederate States of America (CSA) . . . that included three of five US Mints in the South and all of the silver and gold bullion that they possessed. (That included all of the US Custom Houses with millions in coin at hand. It also included the US Arsenal — to produce ordinance — in Augusta, Georgia). The South basically appropriated an existing infrastructure. But despite having three mints and the personnel to run them, they were all shut down in April of 1861.

Cotton was King — and in the beginning, the Confederacy thought it would provide a lot of financial leverage, but that hope waned . . . and as losses mounted in the field, money became scarce . . . supplies dwindled and inflation soared. The Southern Government eventually impressed the public for and supplies — writing IOUs essentially. Then they sought donations . . . In the end, the State of Virginia tried to aid General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia with $300,000 in gold, bit it was too little, too late . . . (Please read “The Furious Flight of the Confederate Treasure Train . . .” for much more about this last-ditch effort as Richmond, Virginia fell.)

To compound the problems, during the “Ten Tumultuous Years” (1857-1867), counterfeiting was running rampant — and by then end of the War, it’s said that 30% of the currency in circulation was fake. The economy was already awash in “funny money” before the War began, but pressure on the US Treasury to do something to combat counterfeiting was a big factor in the birth of the “Greenback,” the distinctive color of green that US Currency took on in 1862. And for a while, sanctioned counterfeiting helped stoke inflation in the South.

And speaking of money and Mints: while the Mints in Dahlonega, Charlotte and New Orleans in the South were being “taken in trust,” the combination of the War’s mounting expenses and the discovery of so much precious metal in the Far West led to new brand mints being authorized — in 1862, ’63 and ’64 — in the Colorado, Nevada and (ready for this) Oregon. That last one — built in The Dalles (near Mt. Hood) — never produced a single dime.

This is just a taste of the goings-on that we explore . . . below are “mini-posters” which are “teasers” for one of the Chapters in Voume 1:

Click Here for the Table of Contents . . .